This has got nothing to do with the Space miniblogs, but 1) I need a distraction from the despair of my beloved Everton getting totalled by Crystal Palace, and 2) I found this on Facebook and it interests me.

In case the text is a bit hard to read, I’m going to reproduce it here and add my comments:

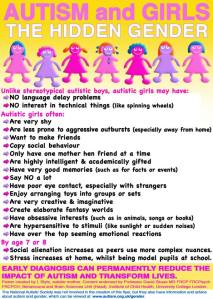

Unlike stereotypical autistic boys, autistic girls may have:

– No language delay problems This is true, I learned to talk quite young – I was about two, I think.

– NO interest in technical things (like spinning wheels) I don’t remember having any interest in ‘technical things’.

Autistic girls often:

– Are very shy Yes, I was pretty shy. Still am.

– Are less prone to aggressive outbursts (especially away from home) I don’t remember having any aggressive outbursts as a kid. Those came later, as a teenager and an adult woman.

– Want to make friends Yes, but it was very hard for me, which goes without saying.

– Copy social behaviour I still do. I have a rather large complex about what is and isn’t the ‘right’ way to do things. I should probably not take behavioural cues from Tumblr, though.

– Only have one mother hen friend at a time I’m not sure what a ‘mother hen friend’ is, but I was the sort of kid who’d have one best mate rather than a large crowd of friends like my brother did.

– Are highly intelligent and academically gifted Yes. I wasn’t a savant, but I did get good grades.

– Have very good memories (such as for facts or events) Yes, and not much has changed there. To quote my brother, “Lotte is an encyclopaedia of family history. She remembers everything.” This actually came in handy recently, regarding my mother, in an event which I am not prepared to talk about right now.

– Say NO a lot I might have. I don’t know.

– Have poor eye contact, especially with strangers Yes, and I still do. If I don’t look you in the eye, I’m either nervous, or I don’t like you. Generally, it’s the former!

– Enjoy arranging toys into groups or sets Yes. Definitely. And later, CDs and books.

– Are very creative and imaginative Yes. I loved writing stories and I read like the clappers.

– Create elaborate fantasy worlds Yes. Mum used to get angry with me for living in ‘my own little world’, and I got upset because I felt like she was attacking the fantasy world in my head where all my characters lived. This wasn’t a DID thing, incidentally. It was more like an imaginary friends thing. I used to play with toys and dolls and make up stories for them, often based on things I’d seen on TV.

– Have obsessive interests (such as in animals, songs or books) Yes. Abba, Asterix books, Sylvanian families, certain TV programmes. When I got older, it was Space, Naruto, Everton FC, the Chalet School series, and many other things.

– Are hypersensitive to stimuli (such as sunlight or sudden noises) Yes. I hated people shouting or loud crowds, and would put my hands over my ears or cry. I’m still the same. The partner in the Manchester office kept shouting at me when I was having a meltdown, and that made it even worse. People ask me how I listen to metal. It’s expected noise, basically. You know the singer’s going to start screaming, plus it often has a nice tune or beat to accompany it. I draw the line at drone, though. Friends of mine love Sunn O))), but I could never get into them for this reason.

– Have over-the-top seeming emotional reactions Yes. At one point, Mum said she was going to take me to a doctor because there was clearly something wrong with me, because I cried very easily.

By age 7 or 8:

– Social alienation increases as peers use more complex nuances Yes. I felt left out a lot of the time, and some girls did take advantage of the fact that I was quite naive and took things literally.

– Stress increases at home, whilst being model pupils at school Yes. Admittedly, a large part of it was my father’s illness, but there was also the fact that my mum was frustrated at my weird behaviour and my brother and I didn’t get on very well a lot of the time.

Credit for this flyer, by the way, goes to L Style, an autistic mother. At the bottom, she has provided a link to the National Autistic Society’s section on gender.